This post also appears at the Log Lines blog of the USS Constitution Museum website.

Think not, you play-goers and lovers of the drama, although a wide waste of waters separates us from those shores where histrionic representations are cherished and admired as they ought to be by all classes, that the inmates of our gallant ship are debarred the pleasures derived from witnessing the heroes of the sock and buskin “tread the boards;” no such a thing. Be it known to you, gentle reader, that amongst our jolly lads we have several who in by-gone days have “strutted their brief hour,” and who, to gratify their three years’ associates, voluntarily came forward to lend their humble aid towards dispelling the dull monotony by which we are surrounded; and the quarter-deck of our trim old frigate, can in a few short hours, as if by the wand of an enchanter, be transformed into a little theatre, which would not be looked on slightingly even by those who are wont to gaze upon the gorgeous decorations of the Bowery or Park.

-Henry James Mercier, Life in a Man-of-War

One of many firsthand accounts of theatricals aboard nineteenth-century ships, Henry James Mercier’s Life in a Man-of-War recounts a series of performances given by sailors aboard USS Constitution while the ship was harbored in Callao, Peru. I learned about this firsthand narrative while researching Herman Melville’s account of a shipboard theatrical in White-Jacket (1850), which–it turns out–is a fictionalized version of Mercier’s account (Huntress 73). In Melville’s telling, the commanding officer of the Neversink, Captain Claret, begrudgingly allows the performance of an original play to celebrate the Fourth of July as the ship approaches the dangerous waters off Cape Horn, only after scanning the play for anything “calculated to breed disaffection against lawful authority” (NN WJ 93). Although the dramatic text passes Claret’s censorship, the performance conjures a “terrific commotion” from the audience that made “all discipline” seem “gone forever” (94). As I argue elsewhere, Melville offers a thrilling fiction that associates performance with danger by appropriating Mercier’s account of performances mounted aboard USS Constitution.

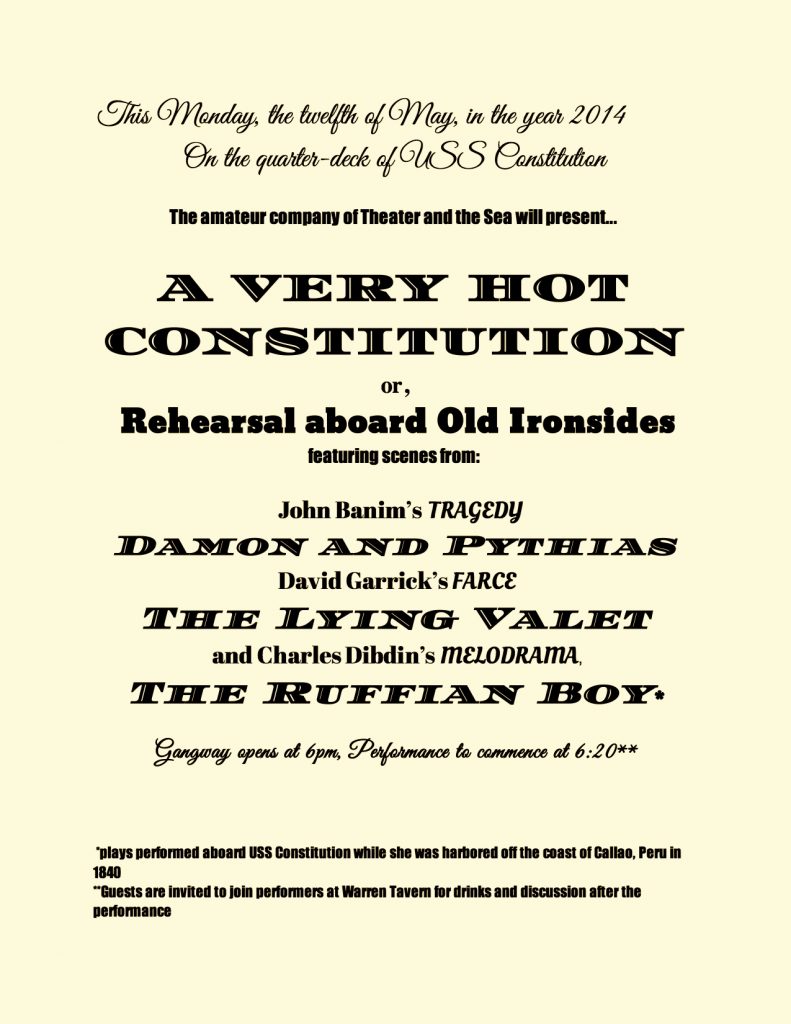

Inspired by this research, I requested permission to stage, with students enrolled in a course at Yale called “Theater and the Sea,” a production inspired by the performances documented in Mercier’s narrative. I was delighted when the commanding officer of the Constitution, CDR Sean D. Kearns, responded with enthusiasm to the idea. The seminar introduced students to the history of nautical drama (including Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore, Eugene O’Neill’s sea plays, Robert Lowell’s Benito Cereno, and Moby-Dick, the opera). We also spent considerable time studying the history of plays performed by sailors at sea. Students prepared production histories on plays that sailors performed, and their research informed the play we wrote together.

We considered many possibilities for our production over the course of the semester. We thought of staging one of the plays, reconstructing how sails and the ship’s rigging might have been used to construct a makeshift theater on the quarterdeck. While this is still a very tempting idea (and a larger production in the future might provide such an opportunity) we decided that we were most interested in imagining what it would have been like for sailors to rehearse in various places around the vessel. We drew inspiration from Timberlake Wertenbaker’s award-winning play Our Country’s Good (1988), a theatrical adaptation of Thomas Keneally’s novel, The Playmaker (1987). The play and novel imagine a 1789 performance of George Farquar’s The Recruiting Officer (1706) in the early days of the Sydney Cove penal colony. Requested by the Governor, the performance was directed by the second lieutenant of the convict ship and the performers were convicts. My students and I were most struck by the way the convicts discussed particular lines from The Recruiting Officer during rehearsals, and we began exploring how lines in the plays performed aboard the Constitution (a farce, tragedy, and melodrama) might have resonated with the sailors performing them.

Instead of rehearsal building toward the performance of one play, then, we imagined preparations for three different plays, representing very different genres popular in the nineteenth century. The plays Mercier mentions are all British plays that had been performed in American theaters in the 1830s. The bill for the ship’s first production included John Banim’s 1821 tragedy, Damon and Pythias, and David Garrick’s 1841 farce, The Lying Valet. Just one week after the debut, the dramatic club offered the 1819 melodrama, The Ruffian Boy, “by particular request of the officers,” and repeated the Lying Valet. Significantly, Mercier emphasizes that officers requested the play, which would have given it a vote of confidence from a class above the common sailor. “So taken were our old sea-dogs with the theatrical mania,” he explains, “that they again set a subscription on foot, and replenished the funds with two or three hundred dollars more” (122). The author of the prologues, in turn, repaid this kindness with two original pieces, “entitled, Life in Peru and Old Ironsides paid off,” which were “met with a warm and hearty reception from our tars, the language and incidents coming so home to their bosoms” (122). No description is offered of Old Ironsides Paid Off, but the title suggests it was a self-referential play about the Constitution returning home. The second play, Life in Peru, seemingly depicted events that occurred during shore leave. Mercier makes no direct mention of female roles, though The Lying Valet would not be The Lying Valet without love-struck Melissa and her comic maid, Kitty Pry. In our rehearsal play, we imagine several situations that might have emerged as male sailors prepared to perform the female roles.

My primary goal with the culminating performance of the course was to give students an opportunity to experience the unique features of shipboard theatricals by actually performing aboard a ship. As I anticipated, it was thrilling to perform aboard the same vessel that served as a venue for shipboard theatricals in the nineteenth century.

The prologues Mercier includes in his account took on new significance after we had embarked on our own production aboard Old Ironsides. I now suspect that Mercier (or a close acquaintance of his) wrote the prologues, which I include in full below:

What cheer, my hearties! Shipmates how d’ye do?

-February 14, 1840

I’ve come to spin a twister unto you;

And tho’ my lingo should, d’ye see, be rough,

I not being graced with grammar or such stuff,

I’ll in my humble style get under way

Knowing you’ll list to what I’m going to say:

Since we from famed Columbia’s shores set sail

Our gallant ship has weathered many a gale,

And buffeting each tempest that we’ve met

She’s proved herself the same trim sea-boat yet

That she was wont to be in days long past,

When she withstood the battle and the blast!

Safe and unharmed the stormy Cape we’ve braved,

Although its gales with fierceness o’er us raved;

And spite of its terrors, which make thousands fear,

We now, thank Heaven, are safely anchored here.–

No doubt you think it is a novel sight

To see Jack Tar strut forth with all his might,

Doffing tarpaulin, and with lightsome heart,

Enact the tragic or the comic part;

But Shakspeare says that ‘all the world’s a stage;’

Why should not we on shipboard catch the rage

as well as those upon the dull tame shore? [gesture at audience]

We strive to please, the best can do no more.

Although our pond’rous guns now passive lay,

Our “spangled banner” spread to grace our play,

Yet should our country but require again

Our services upon the azure main,

I’ll venture that ‘Old Ironsides’ once more

(Her present captain, crew and commodore,)

Would prove herself, as o’er the deep she’d glide,

Columbia’s armament, Columbia’s pride!

There’s now tranquility from shore to shore

And the dread voice of war is heard no more;

Our country’s smiling in the lap of peace,

Her navy and commerce every year increase

And we the sons of war have laid us by

The exercising our artillery;

And armed with pointless swords we now are here

Awaiting your approbation to appear: —

Which should we gain, our efforts will not cease,

But strive with something new each night to please;

For, believe me, the purport of each farce or play

Is but to while the tedious hours away,

To cause a gladsome twinkle in your eye,

And try to dispel the dull monotony

That oft on board of ship doth intervene

And serves to sadden many a joyous scene.

So while we move in our dramatic sphere

Let not your criticisms be too severe;

And should some trivial errors meet your eye,

Mariner like I know you’ll pass them by.

So, shipmates, I’ve told you all I’m going to tell,

For hark! I surely hear the prompter’s bell;

And when my other maties do appear

I hope they’ll meet a kind reception here.

February 22, 1840

Shipmates, I’ve come again before your sight:

For after your plaudits of last Friday night

‘Twould be ungenerous of our Thespian crew

Did we not give our heartfelt thanks to you;

Accept them then on their behalf from me,

Although uncouth and rude those thanks should be;

But the reception of our first efforts met

Believe me, my friends, we never will forget.

Our little corps had enemies enough,

But spite of each frown and spite of each rebuff

We’ve catered once more to please your appetite,

And stand prepared this glorious festal night

To try our luck again; –with you it lays

Either to damn us or to give us praise.

Think to yourself with what a beating heart

We first stepped forth to play our humble part,

Fearful that every criticizing eye

Would in each word or action something spy

To censure and condemn for little cause;

But no, you gave us undeserved applause.

For which we thank you; and our humble band

Are here again waiting for your command

To come before you, and to prove to all,

We’re ever ready to obey your call;

Aye, from this duty we will never flinch–

You’ll find we’ve not relaxed a single inch;

For though our time was short, we’ve something new

I hope will prove acceptable to you;

And if our humble efforts but succeed,

We will feel doubly satisfied indeed.

This is a night to every freeman dear;

And I am sure there’s scarce a bosom here

That does not throb with pleasure and delght,

And hail with rapture, Washington’s birth-night.

This twenty-second, gave that mortal birth

Whose brilliant actions echoed round the earth;

Who, with the flag of liberty unfurled,

Became the pride and wonder of the world;–

In all his deeds, heroic virtue shone;

His friendship, kings and potentates did own;

And he performed so virtuous, his career,

His foes by turns did wonder and revere.

My warmth of feeling, who there will blame,

When eulogising Washington’s great name?

For Britain’s naval sons are too possessed

Of that which fills each guileless, noble breast,

To censure me for my expressions here

When on the subject which we all hold dear.

Grim war now rears his fitful head no more,

But smiling peace extends along our shore;

And as it is the gem with which we’ve dress’d

Columbia’s fruitful, palpitating breast,

May him who’d wish to wrest this gem away,

Become to his impolitic views a prey.

Yes, Heaven, grant this peace may far extend,

And rival nations in sweet union blend;

May Britain and Columbia still go hand in hand,

And show to the world how close their friendship stand;

And strongly cemented by this friendly tie,

They might without fear the very globe defy:

What nations, then, combined in all their might,

Dare stop the lion’s roar–the eagle’s flight?”