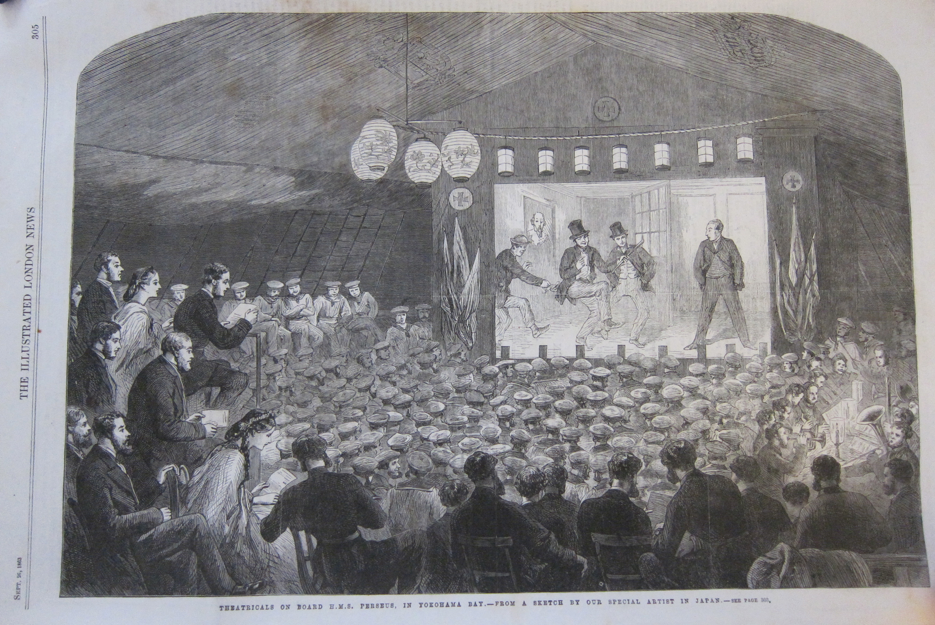

This is my favorite image of a shipboard theatrical. It documents a performance aboard the HMS Perseus as the ship was harbored in Yokohama Bay, Japan in September of 1863. I like it because it conjures the performance event more vividly than written records can. But we actually know far less about this production than others; Charles Wirgman wrote only a brief description of it to accompany his illustration:

On Thursday last H.M.S. Perseus gave a grand entertainment, comprising theatricals, music, and a capital supper. The curtain rose at seven o’clock to a numerous audience, including the Admiral and his Staff and the two Captains of all the men-of-war in the harbour: two ladies also honoured the representation with their presence. the blue-jackets in great numbers squatted on the deck. At the conclusion of the play we adjourned to the banqueting-hall on the quarterdeck where about a hundred guests sat down to supper. All the arrangements were perfect, and the party did not separate until the small hours of the morning.

-Charles Wirgman for The Illustrated London News, September 26, 1863

We don’t know the name of the play performed in this shipboard theatrical, nor who performed it. But there are many more accounts that provide such information. These accounts don’t include illustrations; they are primarily written descriptions that detail the plays performed, the reaction of the spectators and, very importantly, the staging. And while the ships described were broken up long ago, ship plans and muster records remain.

Phase 1: Model the Ship Myself

At the Digital Humanities Summer Institute, I began the process of building a 3D model with the free program, Sketchup. I first learned about digital modeling from Hugh Denard, who presented on the exciting things happening in the field at What signifies a theatre?, a conference on amateur and private performance hosted by the University of London, Royal Holloway in June 2012. After learning about Hugh’s Abbey Theatre project, my first impulse was to begin modeling makeshift venues on my own. Digital modeling offers the best way of answering questions about shipboard staging prompted by limited written sources. A play review in The Young Idea (a shipboard journal edited by a clerk aboard the HMS Chesapeake, circulated to subscribers in manuscript, and then printed by fascimile in London in 1867) explains that, “the stage itself was raised on the Starboard side, between the Mainmast and the Gangway, about 4 feet above the Deck, the orchestra being arranged in front.” My contention was that a digital model of the upper deck constructed from the plans of the Chesapeake and other accounts of staging in the journal would allow me to determine what parts of the ship’s rigging would have proven useful in this transformation and make an informed conjecture about the depth of the stage and the space remaining for spectators. The review in The Young Idea does not specify how many spectators were in attendance (I have not yet come across an account that includes a precise number of spectators), but digital modeling would allow me to fill the space of the deck with virtual sailors, ladies, and gentlemen to determine the shipboard theatre’s capacity for spectators. Working from muster records for these vessels, I could determine in each case how many men were on these ships and model how tightly packed the upper deck could have been during a performance to achieve a much richer understanding of shipboard staging practices. A 3D model could also enable an easy juxtaposition of views: the perspective of the officers and invited guests, who often sat in privileged “royal box” seats near the stage, as compared to the perspective of low-ranking seamen positioned further from the stage.

Phase 2: Partner with Students

At some point in this process, I learned about John N. Wall’s incredible Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, arranged a phone call with Dr. Wall, and started to look for opportunities to collaborate with students. Soon after arriving at the University of New Haven, I made a friend in the Engineering Department, Maria-Isabel Carnasciali, who saw the value in the project for two undergraduate Engineering students who excelled in SolidWorks. In the Spring of 2016, we began our project, “Editing The Young Idea, Modeling the Chesapeake.” The Provost supported our efforts, which allowed us to pay two undergraduate researchers in Engineering to model the ship from plans held at the National Maritime Museum, under Dr. Carnasciali’s mentorship, while an undergraduate researcher in English worked to model the newspaper produced aboard the ship under my mentorship (more on the Digital Young Idea here).

When I began this project, my priority was to implement the methodological principles of the London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage, which “seeks to establish what is required for 3D visualisation to be, and to be seen to be, as intellectually rigorous and robust as any other research method.” The charter emphasizes the importance of intellectual transparency in 3D visualization. Following these principles, I worked hard to link all decisions to sources—ship plans, written records, and artifacts—and document each decision as it occurred. As our project got underway, however, I deferred to Dr. Carnasciali as she transformed the task of modeling a ship from an enormous print copy of the plans into a learning opportunity for her students. They made decisions together on how precise they could afford to be (within a quarter of a foot, not to the precision of small metal pieces) and how best to handle technical difficulties. The result of her students’ work (documented in this report) demonstrates the value of the experience, to be sure. It also revealed that even with the ethical approach of paying students for their work, it is very hard for undergraduate students to find time to devote to a project like this. This experience got me one step closer to developing the Digital Humanities Lab, which places more emphasis on inspiring students to develop their own research projects to be pursued with a faculty mentor through independent studies or summer research fellowships.

Phase 3: Partner with Students in a Gaming Platform

I have long wanted the models emerging from this project to serve as a virtual venue and lay the foundation for actual performances (virtual, mixed reality, or physical). A colleague in Math, when learning about my research, asked if I’d ever heard of Return of the Obra Dinn, a brilliant game set on an East India merchant ship that encourages players to piece together the truth of a crew’s disappearance from sparse (if supernatural) evidence. The timing was perfect for me to learn about this game, because a student in one of my first-year writing courses had just introduced me to machinima as he explored Red vs. Blue as an adaptation of Halo. I was in just the right headspace to begin imagining how a gaming environment could provide the perfect venue for these adventures in modeling. I’m now dreaming about developing this project in a virtual environment like MineCraft. Inspired by Coalchella and Amy Absher’s experiment integrating MineCraft into a “symbolic world” seminar (not to mention WesterosCraft), I think that all I really need is a special topics course and a sense of adventure.