Adaptation is a powerful tool in the literature classroom. What works well when teaching literature does not always work well when teaching writing, but I have found adaptation equally beneficial for both tasks. This is because it interrupts the common student expectation that there is a single story that should be interpreted in a particular way. Theories abound on this phenomenon, but I can share that the practical result for me has always been a benefit. I often begin my first-year writing course with versions of Little Red Riding Hood: “Little Red Cap” (a translation of the Grimm brothers’ version) next to “Little Red Riding Hood” (a translation of Perrault’s version) next to “The Grandmother” (a translation of the French folktale), which David Kaplan turned into a short film starring Christina Ricci in 1997. Though some students might try to hunt for the “right answer” about the meaning of Little Red Riding Hood, they quickly realize that this simply won’t be an option. There is too much variation to pin anything down. And with that important lesson so clearly illustrated, we’re off to the races.

I am able to do this efficiently in the classroom because the brilliant folklorist D.L. Ashliman built an open website, which makes it possible for me to have students discuss the variations through Hypothesis annotations on a single webpage. As much as possible, I try to assign open educational resources in my first-year writing courses. I have learned that this does not mean I need to create it all myself. Ashliman’s site is far more useful than the compilation of texts that I could pull together on my own, primarily because adaptations of Little Red Riding Hood involve translations, and that’s harder to navigate in terms of copyright. After trying for many years to create my own open-source collection of adaptations for teaching in Pressbooks, I am able to appreciate specific features of Ashliman’s editorial approach. His own translation, made freely available to anyone visiting the site, is carefully contextualized with information on and, where available, links to his sources. He provides the information my students need to begin making sense of these texts on their own, which is a major goal in first-year writing courses, where I make it a point not to be seen as the source of “truth” on the texts. I’m not lecturing on the meaning of texts or providing context I’ve gathered in my years of scholarly activity. Students are challenged to pursue their questions with the information Ashliman provides, and he provides just enough for them to do that.

Zotero and Adaptations

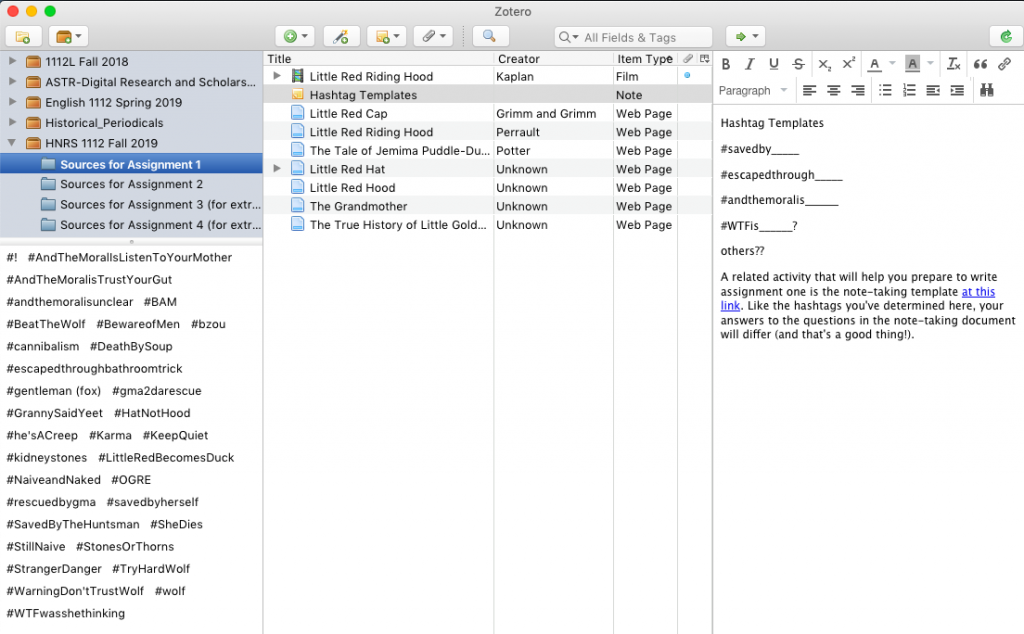

I’ve started to think about other tools (besides Hypothesis annotations) that might allow me to encourage students to develop their own unique angles and approaches to these texts. Inspired by Matthew E. Hunter’s “Against Modules: Using Zotero As a Learner-centered Course Management Tool,” I’ve been thinking about ways to introduce Zotero to my students earlier in the semester. Instead of waiting to introduce Zotero during the research project (the third assignment in the course), I’m now inviting students to join a course group and use the group’s shared library from the start of the semester. This allows me to show them how the interface works over a longer period of time, but it also allows us to experiment with Zotero’s tagging system to identify trends across adaptations, which helps them discover unique angles on the texts. At first, I considered Zotero a separate step from Hypothesis annotations, which I ask students to make before our first discussion. But now I’m thinking that Hypothesis can be worked right into Zotero. I will ask students to make their initial annotations before class, and then give everyone time to read through everyone’s annotations during class before editing their own annotations to add tags. We might discuss possible patterns before or after the second phase of the project. I can then move tags from Hypothesis into Zotero (or ask students to do this) to demonstrate one of Zotero’s powerful mechanisms for tracking analysis.

Great Texts for thinking about Adaptation in First-Year Writing Courses (with notes on use in Lit Courses)

- Benito Cereno (I use the 3-part text as it appeared in Putnam’s Monthly; I also assign the first chapter of Greg Grandin’s The Empire of Necessity, which retells Melville’s story, In a lit class, I’d also assign Robert Lowell’s adaptation)

- Jane Eyre (Incorporate materials from the Rare Book School collection associated with this exhibit; in a lit course, I’d also assign Wide Sargasso Sea)

- Little Red Riding Hood (use D.L. Ashliman’s site)

- Wonder Woman (nothing in the public domain for this project, which made it pretty challenging, but still very fruitful to explore the first issues of the comic, the 70s TV show, and the 2017 film)

- Pygmalion (translations of Ovid alongside clips from Pretty Woman and She’s All That; in a lit class, I’d also assign Shaw’s play and My Fair Lady)

- Antigone (to rely only on open resources, you could use a free translation and contrast with excerpts from Anne Carson’s 2015 translation (have students decide on the selections to contrast based on sections of the text they find interesting/challenging in the original text. If possible, screen Open Art Foundation’s brilliant documentary, We are Not Princesses)

- The 9/11 Commission Report alongside selections from the graphic adaptation of the report

- The Confessions of Nat Turner alongside selections from Kyle Baker’s graphic adaptation alongside The Birth of a Nation (2016)

Student Research Projects

- Hamilton

- Heathers, the Musical

- Cinderella

- Red vs. Blue (machinima based on Halo)

- The Greatest Showman (adapting the life of P.T. Barnum)

- Women in the Military (how has the institution adapted)

- My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

- The King’s Speech

- [and many more]

Producing OER

The power of adaptation studies for teaching literature and writing comes full circle, I think, when we start talking about how we can encourage students in first-year writing courses to find and edit texts with interesting adaptation histories for use by students in the future. This is something I have done in an upper-level adaptation course called The Art of Adaptation in Literature, Games, and Film, but I’m experimenting this semester with a version of this editorial project for freshmen in my first-year writing course. I’ll report back once we’re done!