I think it’s safe to call the distinction between writing to learn and learning to write one of the pillars of writing pedagogy. It is a truth universally acknowledged among writing instructors that we should use low-stakes, informal writing to encourage students to process what they’ve read, seen, or heard. The WAC Clearinghouse at Colorado State University has a fantastic introduction to the concept, and Penn State’s website provides an example of the distinction as it is often articulated to instructors new to teaching writing. The concept is so ubiquitous that I imagined it might already be an established hashtag on academic twitter. A quick search hasn’t turned anything up, but I’ll be investigating this further. Maybe I’ll make it a thing. I think wtl;ltw has a nice ring to it.

wtl;ltw

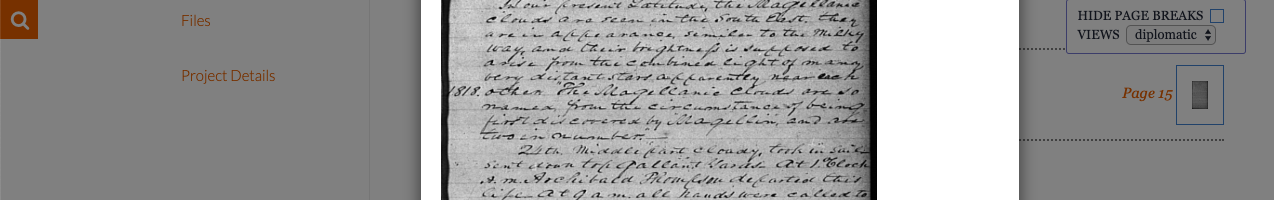

Whether it is established as a hashtag yet or not, writing to learn (wtl) vs. learning to write (ltw) is clearly central to the world of writing pedagogy. I’ve been thinking lately about how the concept might translate to the pedagogy of editing, which I’ve been exploring for some time without theorizing it as such. Scholarly editing has traditionally been taught at the graduate level, but my training began after graduate school, through a series of summer courses, workshops, and very generous guidance from the editors of Scholarly Editing. My interest in scholarly editing began with The Young Idea, a handwritten shipboard newspaper held at the British Library. This artifact ignited a curatorial impulse that I was, at first, unsure how to pursue. Thankfully, I had just enough familiarity with the digital humanities to ask the right questions of knowledgeable people who set me on the right path. Once I had experienced the joys of text encoding and the philosophies underlying the modeling of texts, I wanted to continue having those conversations. I work at an institution without a graduate program in English and there was, not surprisingly, not a single soul at my institution acquainted with the TEI. So, naturally, I decided to get my students interested in text encoding. After my first year at the university, two of my students were awarded summer research fellowships to develop and answer their own research questions by transcribing and encoding The Young Idea. After teaching them the basics over the course of that summer, I realized that I needed to create a semester-long, 3-credit course. That course, Digital Editing, now runs every two years and has yielded some very exciting projects.

I have long argued that we can encourage students to more thoroughly process a whole host of materials by asking them to act as producers rather than consumers of assigned texts. I frequently ask students to think of themselves as editors when they work with platforms like Pressbooks, Hypothesis, and Wikipedia. I have only recently realized that there is a helpful relationship between encouraging students to position themselves as editors (editing to learn; etl) and teaching the conventions of scholarly editing (learning to edit; lte). I made this discovery while preparing my presentation on markup languages for the DH Lab, which is a 1-credit course I created to encourage more undergraduate students to pursue faculty-mentored research projects in the digital humanities.

OER and the etl;lte movement

Ultimately, I think I want to write something more substantial about editing pedagogy and student involvement in the production of open educational resources. I’m now asking myself whether I am more often approaching my assignments as editing to learn exercises or learning to edit exercises, particularly as my assignments (even those I use in first-year writing courses) often lead to actual publication. When I ask students to produce contextual notes and an introduction to a text we’ve all read and discussed (and to direct the introduction and notes to a particular audience), I am not just inviting them to think of themselves as editors for a hypothetical thought experiment. If we choose a student’s edition as a future year’s common read text, that student has worked as an editor. Of course, in practice so far, we assume editorial responsibilities before the material is officially presented to the incoming class. Nevertheless, these students’ ideas shape the experience of a real group of readers. Similarly, when I ask students to create Wikipedia accounts and select an article to improve at the end of my first-year writing course, I am asking them to work as editors for a very real audience (over the last 5 years working with Wikipedia, the 213 articles edited by 111 of my students have been viewed 58.7 million times). However briefly (and expertly), these students have been editors of Wikipedia. In this sense, the only “editing to learn” exercise I give in this class is a reflection on how a particular article might be improved. Students write about what they would do to improve the article, but they don’t actually have to implement their plan.

I thought of these as two separate concepts for a long time. While I encouraged students to think of themselves as editors when improving an article on Wikipedia or preparing a digital edition of a course text as a final project in a literature course, I did not think of these students as doing the same kind of editing that I do. And then I started to teach students how to produce a scholarly edition in an undergraduate course. I realized very quickly that I was emphasizing different things, but there were also some common threads. I’ll be writing more here as I try to sort this out, but I’m thinking that instead of setting the two concepts in opposition (editing to learn vs. learning to edit), it might be more useful to think of the activities on a continuum, or as stop-off points in a recursive process that all editors use.